Where Have All the Identirati Gone? An Identity, Credential, and Access Management Competency Model

Kenneth Myers School of Technology and Innovation, Marymount University IT-810: Applied Research Topics and Methods in Cybersecurity Dissertation Chapter 2

Dr. Donna Schaeffer

Table of Contents

Introduction

Literature Search Strategy

Conceptual Framework

Review of the Literature

Synthesis of Literature Findings

Summary

Works Cited

Glossary

Acronyms

Academic Integrity Statement

Introduction

Identity and Access Management is a vital cybersecurity capability. It is included in multiple academic cybersecurity curriculum and certification knowledge domains. Within the U.S. Federal Government, Identity and Access Management are referred to as Identity, Credential, and Access Management or ICAM (pronounced eye-CAM). This slight variation places additional emphasis on the use of credentials. The Federal ICAM architecture (GSA, 2020) includes five essential ICAM process areas.

- Identity Management – How to collect, verify, and manage identity attributes.

- Credential Management – How to issue, manage, and revoke authenticators bound to identities.

- Access Management – How to authenticate identities and authorize appropriate access to protected resources.

- Governance – The set of practices and principles that guide ICAM functions, activities, and outcomes.

- Federation – Technology, policies, and processes allow an organization to accept identity attributes and credentials managed by a different organization.

The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) identified identity management, a component of ICAM, as a technical cybersecurity competency and referenced the National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST) National Initiative of Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Framework (OPM, 2015) as the primary source for identifying and defining cybersecurity work roles, tasks, knowledge, and skills. However, the NIST NICE Framework (Petersen, Santos, Smith, Wetzel, & Witte, 2020) does not include specific ICAM roles. ICAM-related tasks are usually within broader roles such as system administrator or database administrator.

The Office of Management and Budget requires all U.S. government agencies to implement a specific ICAM architecture called the Federal Identity, Credential, and Access Management Architecture (OMB, 2019). Based on this policy and the discrepancy between OPM and the NIST NICE Framework, a gap exists in that U.S. Federal Agencies are required to implement a comprehensive ICAM architecture yet do not have defined ICAM work roles and competencies to ensure it is implemented and operated correctly. In other words, what ICAM work roles and competencies are needed to implement an ICAM architecture? What are the foundational ICAM architecture areas? If ICAM is identified in its own OMB memo, why doesn’t U.S. federal cybersecurity workforce planning point to ICAM work roles and competencies? The purpose of this paper is to identify an ICAM competency model that aligns with the Federal ICAM architecture using the NIST NICE Framework to design tasks, knowledge, and skills. It will accomplish this by demonstrating a model for creating work roles and competencies derived from a specific cybersecurity architecture. In essence, an organization would orient its cybersecurity workforce based on the cybersecurity architecture it is implementing. The following section will discuss the literature search strategy deployed in writing this paper.

Literature Search Strategy

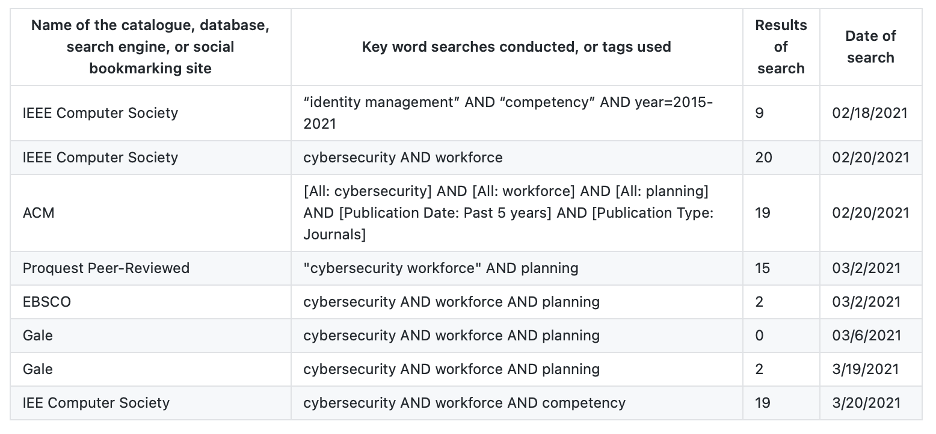

The majority of past and current work specific to ICAM involves general cybersecurity workforce planning or more specific technical ICAM solutions and challenges. This paper’s search strategy employed a three-step process. See figure 1 for literature search strategy results.

- Perform a search from two distinct vectors: cybersecurity workforce planning and identity, credential, and access management topics using a lexicon of ICAM terms mined from the Federal ICAM Architecture.

- Narrow search results by adding modifiers such as publication date in the last five years and publication type.

- Review literature for relevance and applicability.

Figure 1. Literature Search Strategy

Figure 1. Literature Search Strategy

It is interesting to point out the latest ICAM-related topics involve using blockchain technology for distributed identity systems and federation security. As defined in the Federal ICAM architecture, federation is sharing identity information and attributes between organizations. The following section will discuss the conceptual framework researched as part of the literature review.

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework used as part of the literature argument includes five steps.

- Based on the Verizon Data Breach Report (2020), most breach attack vectors exploit an ICAM process.

- ICAM processes are usually implemented using a cybersecurity framework or standards such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, ISO 27000, or other regulatory frameworks.

- Cybersecurity frameworks and regulatory standards are often cited as tasks or knowledge statements regarding work roles. For example, a system administrator familiar with “implementing access control techniques cited in NIST 800-53 Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations”.

- Work roles often include ICAM tasks spread across multiple positions but do not uniquely identify specific ICAM roles leading to a disjointed ICAM implementation.

- Specific ICAM roles are needed to reduce breaches that exploit ICAM processes.

The framework recommends a pivot towards creating a cybersecurity team aligned with the cybersecurity architecture of the organization. In the next section, the paper will review past and current literature on the topic.

Review of the Literature

The literature is divided into three sections to align with the conceptual framework of the literature argument. It starts by identifying sources to ICAM-related adversary tactics, techniques, and attack vectors and then moves to practices protecting data and defend against attacks. The next is on building a cybersecurity team around an implemented cybersecurity framework.

Adversary Tactics, Techniques, and Common Attack Vectors

The top two exploit actions in the 2020 Verizon Data Breach Investigation Report included phishing and stolen credentials (Verizon Enterprise, 2020). Phishing is a technique to trick a user into disclosing information such as a username and password (a credential). An adversary can then masquerade as the user (NIST, 2021c). Stolen credentials are similar to phishing in that credentials are compromised, potentially through a credential database release, and then used to gain unauthorized access to resources. In both examples, a multi-factor authenticator or prompting the user for an additional factor such as a PIN code is implemented to decrease the opportunity to use phished or stolen credentials (Grassi, Garcia, & Fenton, 2017).

Additionally, large organizations may also implement federation to decrease the number of passwords in use and increase multi-factor authentication. Still, this technique can also be abused, as pointed out by the National Security Agency in 2020 (NSA, 2020). This specific type of attack is referred to as the Golden Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) technique and successfully exploited as part of the SolarWinds-related breach activity in 2021 (Reiner, 2020). Tan, Li, Yin, & and Deng (2020) spoke of similar exploits to implementing security protocols but found one main weakness in ensuring “someone who is familiar with the protocol specification and has a well understanding of cryptography and information security should be recruited” to implement authentication and authorization protocol. The same issue is mentioned by Li & Mitchell (2020, p. 670) in regards to implementing well-known federation protocols such as OAuth and Open ID Connect in that “Relying Partys do not always implement OAuth 2.0 correctly; as a result, many real-world OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect systems are vulnerable to attack”. The inverse of this concept would be inconsistent implementation of authentication and authorization protocols could be the leading contributing factor to many credential-related breaches. Authentication and authorization are ICAM processes within Access Management.

Defend Against Attacks Using Cybersecurity Frameworks and Education

Multiple works support the idea that ICAM processes are an essential cybersecurity capability. The Cybersecurity Curricula 2017 are guidelines for post-secondary degree programs in cybersecurity. It identifies identity management, access control, and authentication as crucial areas of broader cybersecurity areas (ACM, IEEE, AIS, & IFIP, 2017, p. 111). Leading certifications include ICAM processes as major knowledge domains, such as 13% of the Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) (ISC2, 2021) exam and 16% of the CompTIA Security+ exam (CompTIA, 2021). The Cyber Body of Knowledge includes an “Authentication, Authorization & Accountability” domain, but it’s one of 19 other domains (University of Bristol , 2020). In addition, there is an ICAM focused non-profit called “IDPro” who published a body of knowledge on the multiple areas of ICAM, including workforce and consumer identity, laws, access control, project management, non-human entities, digital identity, and a few others (IDPro’s Body of Knowledge, 2020). This body of knowledge is an assortment of articles rather than a formal publication, but the goal of IDPro is to eventually make it a formal publication.

In addition to ICAM processes in academic and certification material, it is also included in a number of cybersecurity architectures. Within the NIST Special Publication 800-207 on Zero Trust Architecture, identity governance is one of three approaches to implementing a zero trust architecture (Rose, Borchert, Mitchell, & & Connelly, 2020). The version 1.1 update of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework identified the importance of ICAM process by refining the access control category “to better account for authentication, authorization, and identity proofing” (NIST, 2018, p. 2). The U.S. Government has a specific cybersecurity solution architecture called the Continuous Diagnostics and Mitigation or CDM Program. Phase two of four of the CDM Program focuses on who is on the network and breaks it down into four areas of TRUST (identity proofing), BEHAVE (user security training), CRED (credentialing), and PRIV (privileged account management) (DHS, 2018). These four areas align with the Federal ICAM Architecture (GSA, 2020) of which U.S. Federal Agencies are required to implement the Federal ICAM Architecture potentially using CDM Program integrators. Many standards identify the need to implement potentially advanced ICAM processes. Yet, most sources only provide a basic knowledge of the concept of ICAM processes rather than how to implement them effectively.

Build Your Cybersecurity Team

Cybersecurity workforce planning follows much the same path as academic material. In 2011, Schneider and Mulligan talked about how “Governments, realizing that policy must be a crucial ingredient of any solution, are starting to flex their regulatory and legislative muscle” regarding cybersecurity policies. They concluded government doctrine or direction provided vital support for cybersecurity success (Schneider & Mulligan, 2011, p. 4). We can see U.S. government support in the NIST NICE Framework, which is “built upon a set of discrete building blocks that describe the work to be done (in the form of Tasks) and what is required to perform that work (through Knowledge and Skills)” (Petersen, Santos, Smith, Wetzel, & Witte, 2020, p. 4). Kim, Smith, Yang, & Kim identified the potential of the NIST NICE Framework as a bridge “to find similar academic courses and hire graduating students or find qualified government employees” (2018, p. 4) that align with NIST NICE knowledge, skills, abililities, and tasks. Government support is a crucial enabler, and a framework exists to help define cybersecurity workforce competencies.

Given that so many cybersecurity frameworks and curriculum point to all cybersecurity professionals have a basic understanding of ICAM processes, why aren’t there more advanced courses related to ICAM processes? Very few sources point expressly to “why ICAM” but more generally on the state of cybersecurity curriculum development. Cabaj, Domingos, Kotulski, & Respício share most cybersecurity programs are “aligned with the available faculty and expertise” (2018, p. 35). While this is true that your content may be limited to the knowledge available, they also point to the need to “incorporate more specific security courses into a set of core courses and offer more elective courses” around non-core topics (Cabaj, Domingos, Kotulski, & Respício, 2018, p. 34). Many authors agree that one of the most significant challenges in teaching cybersecurity curriculum is staying current (Bicak, Liu, & Murphy, 2015) (Hoag, 2013). This may be why institutions leverage more adjunct professors in cybersecurity courses than in other domains because they have more current and relevant work experience (Ran & Sanders, 2020).

While multiple publications identify essential ICAM skills and knowledge, they mainly concern broader cybersecurity roles rather than specific ICAM roles. On the same topic, Furnell proposed incorporating a work role maturity model “to recognize the importance of fostering a great community of practitioners at all levels” (Furnell, 2020, p. 6). This maturity model identified six levels from basic to expert, with defined competencies at each level. Given the lack of non-vendor ICAM certifications or training opportunities, it could be assumed that most individuals are trained at the basic level, which may lead to why there are a significant number of breaches that exploit ICAM processes. Gordon (2016) points out that federation is a focus and building block for the cloud security professional, a Federal ICAM architecture domain but excluded from most discussions on access management and access control. This also leads one to see that ICAM processes are more critical when operating a cloud or hybrid architecture. The following section will discuss the synthesis of literature findings.

Synthesis of Literature Findings

Previous work points to ICAM processes as essential and included in various cybersecurity workforce and academic curricula yet not defined as specific work roles in the same fashion as a system administrator or a cybersecurity analyst. Due to the lack of advanced ICAM specific training, it could be assumed that most professionals implementing ICAM processes only have a basic knowledge of ICAM. This may explain why the 2020 Verizon Breach report included ICAM-related attack vectors as two of the top five breach reasons (Verizon Enterprise, 2020). While an ICAM body of knowledge exists, it does not identify how to hire, train, and retain ICAM professionals. An ICAM competency model is needed to highlight the need for ICAM-trained professionals while also closing the gap of ICAM-related exploits.

This paper takes the Federal ICAM architecture as a starting point to build an ICAM competency model. The purpose of this approach is simplicity. If an organization wants to implement this architecture, it seems like a natural fit. Their workforce should be structured in a way to implement and manage it. The Federal ICAM architecture (GSA, 2020) is a U.S. government reference architecture designed for federal agencies. Still, many of the capabilities and services are common for all organizations in that all organizations should manage identities, credentials, and access. Current academic research points to the need for all cybersecurity professionals to have a basic knowledge of ICAM processes. Does basic knowledge suffice to implement and operate advanced ICAM processes? Many indicators point to no in that ICAM-processes are some of the most exploited attack vectors in breaches.

Summary

The literature review intended to introduce and demonstrate a cybersecurity workplace planning model designed around implementing a specific cybersecurity framework or architecture. It helps identify that ICAM processes were essential to cybersecurity curricula, workforce planning, and certification courses. Yet, defined ICAM work roles do not exist or are organizationally defined, which leads to a disparity in determining a clear career path for ICAM professionals. This may lead to further challenges when trying to find “the right fit” for hiring or training employees. While organizations can use this ICAM competency model based on the Federal ICAM architecture, it is not without limitations. The Federal ICAM architecture is written and maintained by and for the U.S. Federal government. It may be updated in the future to further orient itself toward the government rather than fairly agnostic to most organizations.

Works Cited

- ACM, IEEE, AIS, S., & IFIP. (2017). Cybersecurity Curricular Guideline. Retrieved from CSEC 2017: https://cybered.hosting.acm.org/wp/

- Bicak, A., Liu, M., & Murphy, D. (2015). Cybersecurity Curriculum Development: Introducing Specialties in a Graduate Program. Information Systems Education Journal (ISEDJ), 99-110.

- Cabaj, K., Domingos, D., Kotulski, Z., & Respício, A. (2018). Cybersecurity education: Evolution of the discipline and analysis of master programs. Computers & Security, 24-35.

- CIISec. (2019). CIISec Roles Framework, Version 0.3. Retrieved from Charted Institute of Information Security: https://www.ciisec.org/CIISEC/Resources/Capability_Methodology/Roles_Framework/CIISEC/Resources/Roles_Framework.aspx

- CompTIA. (2021). Security+ (plus) certification. Retrieved from CompTIA IT certifications: https://www.comptia.org/certifications/security

- DHS. (2018). PRIVMGMT: The First Step Toward CDM Phase 2 Capabilities. Retrieved from Continuous Diagnostic and Mitigation (CDM): https://us-cert.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/cdm_files/FNR_CPM_OTH_NovWebinarSlides.pdf

- Furnell, S. (2020). The cybersecurity workforce and skills. Computers and Security, 100.

- Gartner. (2021). Gartner Glossary. Retrieved from Gartner: https://www.gartner.com/en/information-technology/glossary/identity-and-access-management-iam

- Gordon, A. (2016). The Hybrid Cloud Security Professional. IEEE Cloud Computing, 3(1), 82-86.

- Grassi, P., Garcia, M., & Fenton, J. (2017). 800-63-3; Digital Identity Guidelines. Retrieved from NIST Special Publication: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-63-3

- GSA. (2020). Federal ICAM Architecture. Retrieved from FICAM Playbooks: https://playbooks.idmanagement.gov/

- Hoag, J. (2013). Evolution of a cybersecurity curriculum. Proceedings of the 2013 on InfoSecCD ‘13 Information Security Curriculum Development Conference - InfoSecCD ‘13, (pp. 94-99).

- IDPro’s Body of Knowledge. (2020). Retrieved from IDPro: https://idpro.org/body-of-knowledge/

- ISC2. (2021). CISSP – the world’s premier cybersecurity certification. Retrieved from ISC2: https://www.isc2.org/Certifications/CISSP

- Kim, K., Smith, J., Yang, T. A., & Kim, D. J. (2018). An exploratory analysis on cybersecurity ecosystem utilizing the NICE framework. National Cyber Summit (NCS), (pp. 1-7). Retrieved from National Cyber Summit (NCS),.

- Li, W., & Mitchell, C. J. (2020). User Access Privacy in OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect. 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), (pp. 664–672).

- NIST. (2018, April 16). Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity. Retrieved from NIST Cybersecurity Framework: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/CSWP/NIST.CSWP.04162018.pdf

- NIST. (2021a). Glossary - Credential. Retrieved from Computer Security Resource Center: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/credential

- NIST. (2021b). Glossary - ICAM. Retrieved from Computer Security Resource Center: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/Identity_Credential_and_Access_Management

- NIST. (2021c). Glossary - Phishing. Retrieved from Computer Resource Security Center: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/phishing

- NIST. (2021d). Glossary - SAML. Retrieved from Computer Security Resource Center: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/security_assertion_markup_language

- NSA. (2020). Detecting Abuse of Authentication Mechanisms. Retrieved from Cybersecurity Advisory: https://media.defense.gov/2020/Dec/17/2002554125/-1/-1/0/AUTHENTICATION_MECHANISMS_CSA_U_OO_198854_20.PDF

- OMB. (2019). Enabling Mission Delivery through Improved Identity, Credential, and Access Management. Retrieved from OMB: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/M-19-17.pdf

- OPM. (2015). Guidance for Identifying, Addressing and Reporting Cybersecurity Work Roles of Critical Need. Retrieved from CHCOC: [https://chcoc.gov/sites/default/files/Attachment%20to%20Memo%20-%20Guidance%20for%20Identifying%20Addressing%20Reporting%20Cyb...pdf](https://chcoc.gov/sites/default/files/Attachment%20to%20Memo%20-%20Guidance%20for%20Identifying%20Addressing%20Reporting%20Cyb...pdf){:target=”_blank”}{:rel=”noopener noreferrer”}

- Petersen, R., Santos, D., Smith, M., Wetzel, K., & Witte, G. (2020, November). National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework. Retrieved from Computer Security Resource Center: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-181/rev-1/final

- Ran, F. X., & Sanders, J. (2020). Instruction quality or working condition? The effects of Part-Time faculty on student academic outcomes in community college introductory courses. AERA Open.

- Reiner, S. (2020, 12 29). Golden SAML revisited: The solorigate connection. Retrieved from CyberArk Blog: https://www.cyberark.com/resources/threat-research-blog/golden-saml-revisited-the-solorigate-connection

- Rose, S., Borchert, O., Mitchell, S., & & Connelly, S. (2020). Zero trust architecture. Retrieved from NIST Special Publication: https://doi.org/10.6028/nist.sp.800-207

- Schneider, F. B., & Mulligan, D. K. (2011). A Doctrinal Thesis. IEEE Security & Privacy Magazine, 9(4), 3–4. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1109/msp.2011.76

- Tan, Y., Li, W., Yin, J., & and Deng, Y. (2020). A universal decentralized authentication and authorization protocol based on Blockchain. 2020 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery (CyberC), (pp. 7-14).

- University of Bristol . (2020). CyBOK Version 1.0. Retrieved from Cybersecurity Body of Knowlege: https://www.cybok.org/knowledgebase/

- Verizon Enterprise. (2020). 2020 Data Breach Investigations Report. Retrieved from Verizon Enterprise: https://enterprise.verizon.com/resources/reports/dbir/2020/

Glossary

- Access Management – The process to authenticate identities and authorize appropriate access to protected resources.

- Authenticator – The means used to confirm the identity of a user, processor, or device such as a username and password, a one-time pin, or a smart card.

- Bound or Bind (Identity) – The process to associate an authenticator with an identity.

- Credential - An authenticator that is bound to an identity through a mechanism such as information on a smart card, a one-time pin app bound to an identity in a directory, or a certificate with personal information. (NIST, 2021a).

- Credential Management – The process to issue, manage, and revoke authenticators bound to identities.

- Federation – Technology, policies, and processes that allow an organization to accept identity attributes and credentials managed by a different organization.

- Governance – The set of practices and principles that guide ICAM functions, activities, and outcomes.

- Identity – A person or non-person entity user.

- Identity Attributes – Contextual information that describes an identity such as name, location, or work role.

- Identity Management – How to collect, verify, and manage identity attributes.

- Identity and Access Management – the discipline that enables the right individuals to access the right resources at the right times for the right reasons (Gartner, 2021).

- Identity, Credential, and Access Management - Programs, processes, technologies, and personnel used to create trusted digital identity representations of individuals and non-person entities, bind those identities to credentials that may serve as a proxy in access transactions, and leverage the credentials to provide authorized access to an agency‘s resources (NIST, 2021b).

- Non-Person Entity – A non-human entity in cyberspace such as an organization, a server, a website, or an application.

- Security Assertion Markup Language - An XML-based security specification developed by the Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information Standards (OASIS) for exchanging authentication (and authorization) information between trusted entities over the Internet (NIST, 2021d).

Acronyms

- IAM – Identity and Access Management

- ICAM – Identity, Credential, and Access Management

- NICE – National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education

- NIST – National Institute of Standards and Technology

- OPM – Office of Personnel Management

- SAML – Security Assertion Markup Language

Academic Integrity Statement

This is an original work researched and written by the author, Kenneth Myers.